Liquid Death

Tuesday, April 17, 2012 at 09:42AM

Tuesday, April 17, 2012 at 09:42AM Part 1 of 2

17 April 2012

In early 2011, a dozen people died after drinking “clairin” – a traditional Haitian alcohol drink – made with methanol in the Fond Baptiste region, north of the capital. Another 20 or so were blinded or paralyzed.

One year later, Haiti Grassroots Watch (HGW) exposes that judicial, health and commerce authorities have not investigated who was responsible for the tragedy. The production and sale of clairin – and “fake clairin” – continues with no regulation. The tragedy could occur again at any moment, on an even larger scale.

Lack of political will? Incompetence? The results are the same.

“It’s like my guts were ripped out.”

That’s how Michaelle Hilaire remembers it.

“I took my cousin to the hospital. While I was waiting at the gate, he died in my arms. When I came home that Wednesday, they told me my brother was ill. I burst into tears. The next day, he was dead. And then, my husband died…. My cousin died, my brother died, my man is dead."

Mother of six, Michaelle Hilaire is one of a group of women from Fond Baptiste, in the mountains above the capital, suddenly widowed or made the wife of a paralyzed or blinded man.

In February 2011, a Fond Baptiste woman died suddenly after drinking clairin – a traditional Haitian alcohol made from sugar cane. In the days that followed, at least 11 others died, and more than 20 others in the same region or in nearby Lully and Lafiteau – most of them men – were made blind or paralyzed.

The national and international health authorities were notified and after field visits, they wrote a report pinpointing a “false clairin,” made from or mixed with methanol, a toxic alcohol generally used as a solvent.

“The tests on patients’ blood samples and on two samples of the alcohol confirmed that methanol is responsible for the poisoning of the residents of Fond Baptiste and neighboring regions,” a February 18, 2011, report said.

Another report from the same period, by Cuba’s National Toxicology Center, laid out the gravity of what had just occurred in the tiny mountain village:

“Methyl alcohol or wood alcohol [is]… the simplest of all alcohols. It is a clear and volatile liquid, with an odor that resembles ethyl alcohol. It is used as an anti-freeze, as a gum solvent, and also in the fabrication of organic products.”

“It is sweeter and much more sugary tasting than ethanol,” Dr. Ancio Dorcélus told HGW in a recent interview. Dorcélus saw the results of that sweetness first hand. He treated some thirty people who had been poisoned, but not killed, at his Arcahaie clinic.

A year later, but like yesterday…

The widow Hilaire doesn’t hide her emotions when talking about her three deceased family members. Tears in her eyes, she tries to remember those days that sunk her household into darkness.

“I had just come from the ‘Pierre’s Home’ marketplace,” she remembered.

“I saw that my husband hadn’t yet awoken. Later, he opened his eyes and asked me to take him to the hospital because he couldn’t see anything, and he couldn’t even stand up, either. His legs were wobbly,” Hilaire continued. He died not long after.

Some of the Fond Baptiste widows. Photo: HGW

Most victims are women, with three to five children. Nowadays, most of these fatherless children don’t attend school. The widows begged a journalist to help them get the government to intervene in order to obtain justice for their dead, blinded or paralyzed partner.

Hilaire knows who sold the mortal drink and is tempted to wrest her own “justice” if authorities don’t intervene.

“If I had someone who would do it with my, I’d get my own justice. But so far I haven’t found anyone,” she said.

The septuagenarian Orinvil Olipré certainly can’t be of help. Blind and half-paralyzed, he sits on a straw mat all day near his small wooden house, listening to the noises that surround him.

Once a farmer who made his living from his fields and a few farm animals, now Olipré is completely dependent on his children. With trembling arms, and despite the damage caused by “methanolized” clairin, he tips his head back to take a sip.

Orinvil Olipré on his mat. Photo: HGW

“Clairin helps keep me warm. It’s really cold up here,” the old man explains.

It would be difficult for the Louis family to help, too, since they lost two men in one week. Veillé Louis’ brother died suddenly, and as he was making the coffin for him, he sipped clairin in order to help him work harder and faster. He never finished.

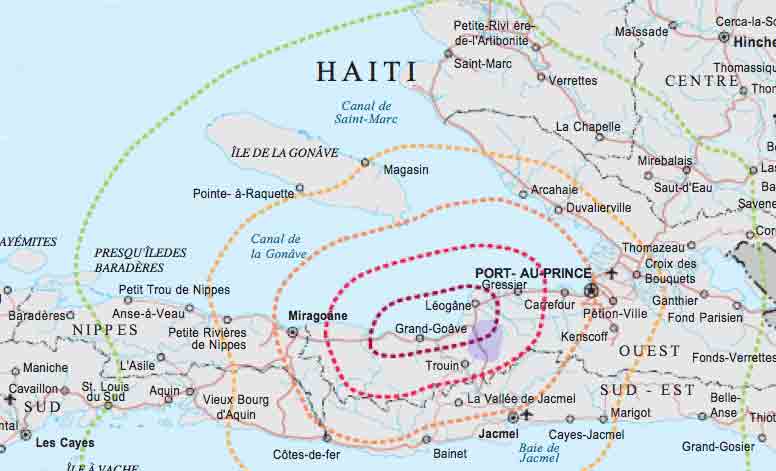

Perched on a mountain 1,500 meters above the sea, Fond Baptiste sits in one of the “communal sections” or rural districts, of Arcahaie, the coastal town where Haiti’s first flag was reportedly sewn. The slopes are covered with fruit trees. Residents live by raising cows and other animals, and by growing vegetables and staples like potatoes.

Because of its cold temperatures, drinking clairin at all hours of the day is very common. People drank the poisoned clairin as they labored in workshops, pruned their trees, or chatted with neighbors on a porch.

Not surprisingly, the hamlet has few services or infrastructure like a hospital or a police station. In fact, there is not one single police officer assigned to the region. And, as across all Haiti, no control over consumer goods.

The sale of clairin

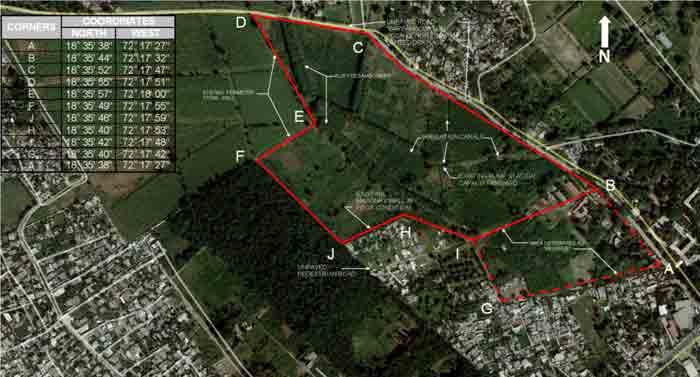

Investigations by the Haiti Grassroots Watch (HGW) team indicate that the Williamson marketplace – at the edge of the city of Cabaret, also in the Arcahaie commune – might be the origin of the “liquid death.” During visits, HGW journalists noted that there were no evident controls placed on the sale of clairin. Wholesalers and retailers did not label their products and there were no signs of any government agent doing inspections.

Clairin in gallon bottles, ready for sale in a marketplace near Léogâne.

Photo: Jude Stanley Roy

Some clairin sellers add pieces of bark as “cures” for various presumed illnesses like menstrual pain or sexual impotence. Wholesalers usually transport their product in plastic 50-gallon barrels, and use old Coke, water or other bottles when selling to retailers or consumers.

Yolette Elien used to sell clairin. She told HGW that the two most popular types are “Sonson Pierre Gilles” from Cabaret and “Guys’ little hard-on” from Saint Michel de l’Attalaye.

“The sellers do whatever they want,” said Elien, who decided to change businesses after being threatened by relatives of poisoned clairin victims. Today she sells books and school supplies.

“Generally, Sonson Pierre Gilles clairin is mixed with boiled water. The same is true for other clairins, like ‘Guy’s little hard-on,” because it is so strong. The secret is in the mix,” Elien explained.

“Nobody from the government has ever come by to see how the merchants sell their product in the marketplace. Everyone does whatever he or she wants, so they can make more money,” she added.

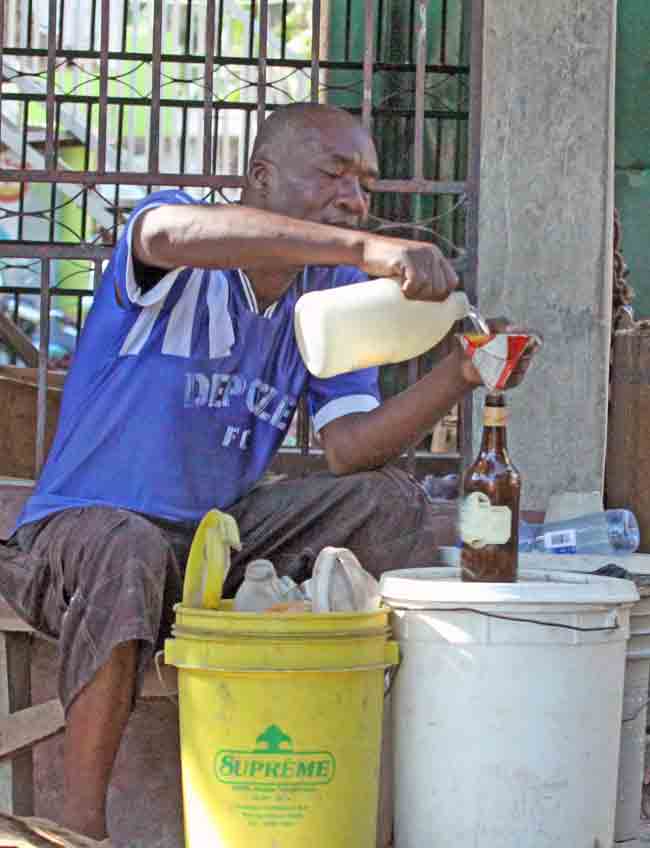

Jean-Claude Joinvil fills an old rum bottle with clairin for a customer

at a marketplace near Léogâne. Photo: Jude Stanley Roy

Sonson Pierre Gilles is one of the most expensive clairins on the market. The more it’s watered down or diluted with something cheaper, the higher the profit.

Deadly mix

The methanolized clairin tragedy isn’t the first time a modified clairin has been sold by ruthless businesspeople.

During the 1990s, after the government lowered tariffs on sugar and other products, certain large import firms and merchants saw an opportunity. They imported foreign ethanol and started selling it as clairin, at half the price of the locally produced beverage. [See “Fake Clairin”]

Last year, the importers and sellers used a much more toxic alcohol: methanol.

“This problem doesn’t occur in urban areas,” explained Dr. Ancio Dorcélus, who treated many victims. “These kind of things happen in the backwoods, far from the capital, for the simple reason that the urban population isn’t going to drink ‘fake clairin.’ They’ll pay for the more expensive, real clairin. Villagers, who come down from the mountains, will buy the least expensive product.”

A typical view from Fond Baptiste. Photo: HGW

“Methanol should not be in Haiti. It is such a toxic product – even just inhaling it can cause death,” continued the doctor who today works for WHO/PAHO (World Health Organization/Pan-American Health Organization). “The odor alone can make you blind, by killing your optic nerves. Whether you breathe it in, or absorb it through your skin, this product is dangerous.”

Dangerous… but legal in Haiti.

But the new Minister of Public Health and Population doesn't seem to know that. Speaking to journalists recently, Dr. Florence D. Guillaume declared that the sale of methanol was strictly “prohibited” on Haitian soil.

“And in any case, these products don’t fall from the sky. One must control the ports and borders in order to resolve this situation,” she pronounced for the microphones.

But she is wrong. Methanol is completely legal.

“The sale of methanol is absolutely not illegal. Methanol is used all over the place. One must not confuse methanol with ethanol. Methanol is used in industry, in woodworking,” Clermont Ijoassin, director of Overseas Commerce for the Ministry of Commerce, told HGW in an interview in February 2012.

“The only alcohol which is subject to import rules is ethanol or ethyl alcohol. Our ministry does not regulate methanol in any way,” Ijoassin added.

Either Dr. Guillaume was misinformed, or she does not remember chemistry class, or she was trying to dissuade the journalist from his investigation.

Difficult to know.

And unfortunately, that was not the first, nor the last, unsubstantiated or erroneous declaration in the liquid death tragedy.

See “Fake Clairin”